This guide outlines the operation of Queensland’s Building Industry Fairness (Security of Payment) Act 2017 (BIF Act), which is designed to ensure cash flow security for contractors, subcontractors and suppliers across the state’s construction industry. It provides a detailed overview of the Act’s key provisions, including payment claims and schedules, reference dates, adjudication processes, and enforcement mechanisms. With strict deadlines and non-negotiable compliance requirements, the BIF Act establishes a statutory right to prompt payments and a streamlined dispute resolution process. Holding Redlich’s Security of Payment handbook is a resource for understanding and applying the BIF Act in real-world scenarios.

The Building Industry Fairness (Security of Payment) Act 2017 (Qld) (BIF Act) establishes a statutory framework designed to promote cash flow certainty and protect the rights of contractors, subcontractors and suppliers in Queensland’s construction industry. The Act imposes strict payment obligations, provides mechanisms for resolving disputes efficiently on an interim basis and introduces penalties for non-compliance.

This handbook serves as a practical guide to navigating the BIF Act, providing a structured analysis of its key provisions, compliance requirements and enforcement mechanisms. It outlines the rights and obligations of claimants and respondents, details the process for making and responding to payment claims, and examines the adjudication and enforcement pathways available under the Act. This resource is designed to assist industry professionals in mitigating risk, ensuring compliance and leveraging the Act’s protections to secure timely payment.

This handbook is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the content should not be relied upon as a substitute for professional legal advice. The application of the BIF Act depends on specific contractual and factual circumstances, and readers are encouraged to seek independent legal advice tailored to their individual situations.

The BIF Act applies to parties engaged in construction contracts for work performed, or goods and services supplied in Queensland. The statutory protections extend to:

The Act is contractually based, meaning it applies where a construction contract exists – whether written, oral or partly both. However, a ‘construction contract’ is broadly defined in the BIF Act and there is no requirement for a formal, signed agreement. Parties cannot contract out of the BIF Act’s provisions.

The BIF Act applies to a broad range of construction activities, including:

The Act also extends to the supply of goods and services related to construction, provided those goods are intended to be used in carrying out construction work. This includes the supply of prefabricated components, concrete and other construction materials, as well as services such as equipment hire with an operator.

While the BIF Act is far-reaching, certain types of contracts and work are outside its scope:

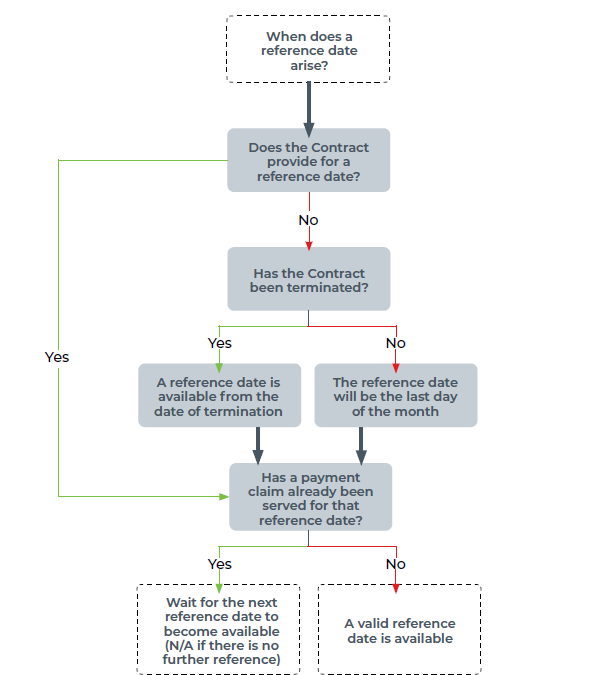

A reference date is the date on and from which a party is entitled to submit a payment claim.

A valid reference date is a statutory pre-condition to making a payment claim. If a reference date isn’t available (or has been used up as only one payment claim can be served per reference date), a payment claim cannot be made until the next reference date has accrued.

Section 67(1) of the BIF Act provides that a reference date will arise on:

Importantly, only one payment claim can be served on or from each reference date, meaning that if a payment claim has already been served for that reference date, the claimant will need to wait for the next one to have accrued.

A date specified in the contract for the making of ‘progress claims’ will be the reference date for the purposes of the BIF Act unless the contract expressly provides otherwise.

Section 70 of the BIF Act provides that a person can serve a payment claim from a reference date. When read with sections 64 and 68, this means that a payment claim must be served on or after the reference date. This overrides contractual provisions that requires a progress claim to be issued on a particular date.

However, several contracts (including the Australian Standard contracts), may provide that a payment claim served earlier than a reference date is deemed to be made on the reference date (a deeming provision).

However, even if a contract does contain a deeming provision, a payment claim cannot be served before the reference date for the purposes of the BIF Act. This is because a deeming provision cannot modify the operation of the BIF Act.

Many construction contracts include preconditions on the right to lodge progress claims or when progress claims will be valid. These include things such as:

While these preconditions may be valid from a contractual point of view, they fall awry of section 200 of the BIF Act, which prevents parties from contracting out of the Act.

This means that even if your contract has a precondition before a progress claim can be served, compliance with this precondition may not prevent the contractor from serving a payment claim under the BIF Act.

A progress payment under a construction contract becomes payable on the day provided for in the contract or, if the contract does not provide for the matter, 10 business days after the day a payment claim is made.

However, the BIF Act mandates maximum payment timeframes if the construction work constitutes “building work” under the Queensland Building and Construction Commission Act 1991 (Qld) (QBCC Act), that will override any conflicting contractual terms:

Any “pay when paid” provisions will be void and unenforceable.

A respondent must issue a payment schedule within 15 business days of receiving a payment claim (or such earlier time as provided for in the contract – see Payment Schedules below). If a payment schedule is not provided within this timeframe, the full amount claimed becomes due and payable on the due date for payment (as determined above). If the respondent does not pay the full amount:

If an adjudicator determines that a payment is due, the respondent must pay the adjudicated amount within five business days of receiving the decision or such later date as allowed by the adjudicator.

Failure to comply with an adjudication determination exposes the respondent to significant enforcement risks, including but not limited to:

Failure to meet statutory payment deadlines can have serious legal and financial repercussions, including:

The longer of these two periods applies.

Essentially, the claim deadline is either what the contract allows or six months from when the work was last done — whichever is longer.

A payment claim is a written document which identifies the construction work or related goods and services, to which the progress payment relates, stating the claimed amount and requesting payment of the claimed amount.

Where a payment claim fails to include sufficient identification of the work being claimed, the payment claim will be invalid.

In considering the requirements to determine whether a payment claim sufficiently identifies the construction work or the related goods and services being claimed, the court has found the test is an objective one. Particularly, the court has found that “the focus must remain on the objective circumstances, not on the subjective intentions of the parties, although it is not wrong to examine the issue from the vantage point of the parties to the particular contract”.

Whilst payment claims (and payment schedules) are not required to be as precise and particularised as court pleadings, the preferred view is that in Queensland, precision and particularity must be required to a degree reasonably sufficient to apprise the parties of the real issues in dispute.

A payment claim must request payment of the claimed amount.

Something that amounts to a request for payment needs to be expressed in the payment claim or necessarily and clearly implied in that document.

Terms such as “amount due this claim” have been held to not be a sufficiently clear request for payment.

However, section 68(3) of the BIF Act provides that if a written document bears the word ‘invoice’ it is taken to be a request for payment, and will avoid this risk.

Section 75(2) of the BIF Act provides that a payment claim, unless it relates to a final payment, must be given before the end of whichever of the following periods is the longest:

Recently, the Queensland Supreme Court determined that complying with the statutory timeframes under section 75(2) is a basic and essential statutory requirement.

Alternatively, pursuant to section 75(3), if the payment claim relates to a final payment, the claim must be given before the end of whichever of the following periods is the longest:

Section 102(1) of the BIF Act provides that a payment claim is authorised, or required, to be given to a person in the way provided in the contract.

However, this provision is in addition to the provisions of any other law about giving notices, like section 109X of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), and section 39 of the Acts Interpretation Act 1954 (Qld) (Acts Interpretation Act).

Section 39 of the Acts Interpretation Act provides that a document may be served:

There is Queensland case law that creates doubt as to whether email is a ‘similar facility’. The risks of this can be managed by the parties agreeing to email as a means of service in the contract but in agreeing to email service, parties should be wary that prior conduct (such as using the relevant email address to send previous invoices) could amount to implied consent to email service.

Service by Acconex (or by some other document management software) is not specifically permitted by section 39 of the Acts Interpretation Act, however, this service is effective where the contract permits service by that method.

However, if something is uploaded to Acconex as ‘sent’, it does not automatically mean ‘served’. Case law suggests that the person to be served becomes aware of the contents of the payment claim when the person logs in to the Aconex website to download or access the payment claim.

Regarding service via Dropbox, the Queensland courts have formed the view that Dropbox was simply not sufficient for the purposes of section 79 of the BIF Act or section 39 of the Acts Interpretation Act as it did not result in the ‘person to be served becoming aware of the contents of the document’.

This means that Dropbox, or any form of link where the recipient needs to click on a link to download a file, particularly so where the document needs to be served within a particular time, should be avoided when serving documents.

Following a recent New South Wales Court of Appeal decision, the position in New South Wales regarding service of a payment claim via electronic means is different to that of Queensland. In New South Wales, service of a payment claim will be effective when the claim is sent and capable of being retrieved, including where a payment claim is capable of being retrieved on an agreed communication platform used by the relevant parties. This means that, irrespective of when the relevant party becomes aware of receipt of a payment claim, time will begin to run from the moment a payment claim is capable of being retrieved on the agreed platform, even if the payment claim is served outside of business hours.

Recent court decisions have confirmed that adjudicators will not have jurisdiction to determine adjudication applications for payment claims which relate to unlawful contracts such as contracts to perform “building work” for which a licence is required pursuant to the QBCC Act but is not held by the claimant. This means that if a contractor is performing work for which they do not hold the appropriate licence, or which was not performed by others pursuant to any statutory exemption, they will not be able to avail themselves to the remedies set out in the BIF Act.

A payment schedule is a written document where the respondent responds to a payment claim.

Section 69 of the BIF Act provides that a payment schedule must:

Section 69(c) of the BIF Act requires the respondent, when submitting a payment schedule, to state all reasons for withholding payment.

The Queensland courts have addressed the extent of reasons for withholding payment required in a payment schedule. Specifically, where a payment schedule doesn’t include any reasons to challenge the valuation of the amounts claimed in the payment claim, this is considered accepting the valuation of works claimed in the payment claim.

Additionally, there are consequences for respondents who provide no reasons, or insufficient reasons, for withholding the whole or part of the claim:

In Queensland, the Courts will not infer reasons from ancillary documentation. Therefore, payment schedules should clearly indicate what is being disputed and why it is being disputed within the payment schedule document itself.

A payment schedule must be given within the earlier of the period specified under the contract or 15 business days after receiving the payment claim.

A recent New South Wales Court of Appeal decision reaffirms the importance of prioritising the statutory timeframes over contractual terms, particularly deeming provisions in construction contracts. In this case, the relevant deeming clause purported to extend the statutory period for providing a payment schedule. Ultimately, the Court of Appeal found that the statutory period could be contractually shortened but not lengthened, and therefore, as the payment schedule was served outside of the statutory timeframe, it was served out of time.

As expressly provided for in section 77 of the BIF Act, if a payment schedule is not issued within time, the full amount becomes due and owing on the due date for the progress payment. Therefore, it is important that any period specified under a construction contract to provide a payment schedule is not inconsistent with the 15 business day requirement in the BIF Act.

For section 78 of the BIF Act, if the respondent provides a payment schedule which schedules an amount for payment, the respondent is required to pay the scheduled amount by the due date for payment.

In either of these scenarios, section 78 of the BIF Act provides three options for the claimant if the respondent fails to make payment of the amount owed by the due date for payment. They can either:

Prior to commencing court proceedings to recover unpaid portions of the amount owed, the claimant must first give a ‘warning notice’ under section 99 of the BIF Act. The warning notice must:

However, by giving the warning notice, the claimant isn’t obliged to start proceedings if they are not paid the amount. Further, the warning notice only provides the respondent with an opportunity to pay the amount owed. It does not give them a second chance to provide a payment schedule.

Pursuant to section 100 of the BIF Act, judgment in favour of the claimant is not given unless:

It is important to briefly provide further qualification regarding the due date for payment under the contract, which is explained below.

As covered in section 5.2 of this handbook, if the work under the contract is, or includes, ‘building work’ for the purposes of the QBCC Act, sections 67U and 67W of the QBCC Act will apply, which provides that certain due date provisions will be void if they are longer than what the QBCC Act allows. Specifically:

Therefore, if either of these situations applies, the due date for payment under the BIF Act will be 10 business days (being, the default position).

The second qualification is that if the contract provides that the due date for payment is a date on which the head contractor gets paid up the line (a pay when paid provision), this is also void.

However, it is important for claimants to understand the due date for payment, otherwise they may be out of time to apply for adjudication or issue a section 99 warning notice as a precursor to applying for judgement. Alternatively, it is also important for the respondents because they could unwittingly contravene the BIF Act by failing to pay by the actual due date.

If a claimant applies for judgment under section 93(1), the respondent will not be entitled to raise any defence, set-off or counterclaim under the contract. The option of applying for judgment is less attractive when the works are still progressing due to the potential for the judgment to essentially be reversed in a subsequent payment schedule issued under the contract in response to a payment claim.

By comparison, in that scenario it can be more beneficial to apply for adjudication, because the claims will be valued by the adjudicator (a task the court does not perform in a judgment application) and any subsequent adjudicator will be required to apply that same valuation.

Pursuant to section 96 of the BIF Act, the claimant has a statutory right to suspend work if they have not been paid the amount owed by the due date for payment. The process for suspension is as follows:

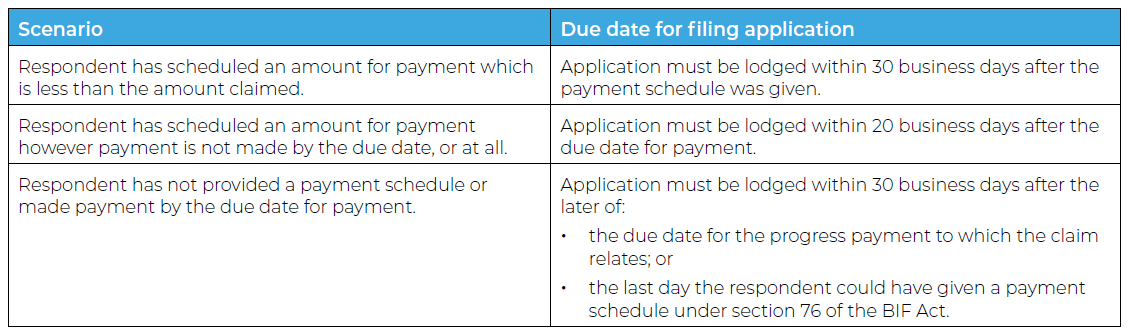

A claimant can make an adjudication application if:

An adjudication application must be made within 30 business days of:

An adjudication application must be made within 20 business days of the due date for payment where a payment schedule is provided with a scheduled amount that is not disrupted by the claimant, but that amount is not paid by the due date.

Pursuant to section 79 of the BIF Act, the right for a claimant to apply for adjudication arises where:

There is an application fee which must be paid upon lodgement. The fee payable depends on the value of the progress claim (inclusive of GST), rather than the value of the amount in dispute.

The period for lodging the adjudication application is dependent upon which of those rights to an adjudication is applicable. This is set out below.

Pursuant to section 79(2) of the BIF Act, an adjudication application:

The approved form means the adjudication application needs to be lodged with the QBCC, accompanied by a QBCC adjudication application form. The form includes:

In Queensland, an adjudication decision will be invalidated where the form the claimant gives the respondent as part of the adjudication application is not the ‘approved form’.

The claimant has three options when making an adjudication application. They can:

However, the final option has been controversial.

The form in this option is a document which is automatically generated by the Adjudication Registry and provided to claimants after they electronically make an adjudication application. The form produced is not identical to the approved form.

The Queensland courts have found that the automatically generated document which follows the online submission process of the application can result in a full copy of the adjudication application never being served on the respondent and therefore, potentially resulting in the adjudication decision being invalidated.

To avoid this risk, the form (which is seven pages) should be downloaded, filled out and included in full (i.e. all seven pages of the form) in the adjudication application that is lodged with the QBCC and served on the respondent.

Although the term ‘submissions’ is not defined within the BIF Act, it includes legal submissions, evidence to support the claim such as statutory declarations or witness statements, expert reports or other similar documents.

The New South Wales Supreme Court has found that a claimant cannot deprive a respondent of specific details in a payment claim and then seek to later provide these details in an adjudication application. Therefore, submissions in the adjudication application need to be supportive of what is already in the payment claim. However, the New South Wales Court of Appeal determined in 2025 that there is no rule prohibiting an adjudicator from considering material not supplied with a payment claim merely because the material would have affected the payment schedule.

The adjudication application and any submissions, must be served on the respondent within four business days after the claimant makes the adjudication application.

A failure to serve the application on the respondent with the approved form is enough to mean that the adjudication application will result in ineffective service, invalidating the adjudication decision that follows.

In addition to ensuring that the entire seven page approved form is served on the respondent, it is also important to ensure that all relevant supporting documentation is served. This issue was recently considered by the Queensland Court of Appeal in Platform Constructions Pty Ltd v Fourth Dimension Au Pty Ltd (Atf Bd Hope Unit Trust) [2025] QCA 264. In this case, the Court of Appeal determined that the adjudication decision was void due to the applicant’s failure to serve a complete copy of the adjudication application lodged with the QBCC on the respondent (seven files comprising the subcontract had not been sent by the applicant to the respondent).

Section 102 of the BIF Act prescribes the method for serving notices or documents referred to under Chapter three of the BIF Act and permits service:

Pursuant to sections 79(5) and 80 of the BIF Act, once the adjudication application is lodged with the QBCC Adjudication Registrar (Adjudication Registrar), it must be referred to an adjudicator within four business days.

Once that referral has occurred, the adjudicator then can accept or reject the appointment in writing to the Adjudication Registrar, but they need to do so within four business days after the referral is made unless they have a reasonable excuse.

If the adjudicator doesn’t accept or reject the appointment within those four business days, the Adjudication Registrar can refer it to another adjudicator who can also accept or reject the appointment.

Section 83 of the BIF Act provides the time for making an adjudication response. Specifically:

Under section 64 of the BIF Act, a complex claim is defined to mean a payment claim for an amount more than $750,000 (exclusive of GST) or, if a greater amount is prescribed by regulation, the amount prescribed. A standard claim is therefore a payment claim for up to $750,000 (exclusive of GST).

The maximum extension permissible is an additional 15 business days.

To be able to claim an extension, the respondent must request the extension of time in writing and within five business days of receipt of the application or two business days after receipt of the adjudicator’s notice of acceptance of the adjudication, whichever is later.

The request also needs to include reasons for requiring the extension of time.

Pursuant to section 84(1)(b) of the BIF Act, an adjudicator must decide the extension of time application as quickly as possible.

An adjudication response must be in writing, identify the adjudication application to which it relates, and include submissions relevant to the response that the respondent chooses to include.

However, in line with section 82(4) of the BIF Act, submissions are restricted to the extent they relate to reasons for withholding payment included in the payment schedule, and a 2025 Queensland Supreme Court decision confirms that where the reasons have not changed from earlier claims, the reasons must still be repeated or identified in each subsequent claim as the narrow scope for challenging adjudication decisions is limited to jurisdiction matters.

Under section 83(6) of the BIF Act, the respondent must serve a copy of their adjudication response with the claimant within two business days, after providing it to the adjudicator.

An adjudicator must decide, within the required time, whether they have jurisdiction to adjudicate the adjudication application and whether the application is frivolous or vexatious.

If the adjudicator decides they have jurisdiction and the application is not frivolous or vexatious, the adjudicator is to decide, within the required time:

In making the determination, the adjudicator can only consider:

If the adjudicator does not consider submissions that were of significance, the adjudicator may have failed to comply with the essential requirements of the Act and the decision is liable to be set aside.

Section 88(3) of the BIF Act prohibits an adjudicator from considering reasons not included in the payment schedule.

Further, an adjudicator may disregard an adjudication application or adjudication response to the extent that the submissions or accompanying documents contravene any limitations relating to submissions or accompanying documents prescribed by Regulation.

These limitations include things like, if the payment claim seeks a payment of no more than $25,000:

Ultimately, an adjudicator must make a genuine attempt to come to a determination on the factors set out in section 88(2) of the BIF Act and “turn their minds to, grapple with and form a view on all matters that they are required to ‘consider".

In reaching this decision, the adjudicator may:

Out of these options, it is most common for the adjudicator to request submissions and set deadlines in respect of those.

Under section 84 of the BIF Act, the adjudicator must decide an adjudication application as quickly as possible, but in any event no later than:

The response date is the date the adjudication response was given, or the due date for the response, whichever date is earlier. The due date of the Adjudicator’s decision can be extended by agreement if both parties agree to extend it before the original due date for the decision.

If the application relates to a complex claim and the parties don’t reach an agreement on the extension, the adjudicator can unilaterally extend the time by five business days only. The adjudicator must give notice of any extension to the Adjudication Registrar within four days of getting the extension.

Whether an adjudicator has fulfilled their duties set out in section 88(2) of the BIF Act is often relevant as to whether they have ‘valued’ the construction work.

Specifically, under section 72(1)(a) of the BIF Act, if a contract provides for how the construction work is to be valued, the adjudicator must value the construction work in accordance with the contract. The same applies to the value of related goods and services, provided for in section 72(2)(a) of the BIF Act.

If, on the other hand, a contract does not provide for how construction work carried out under the contract is to be valued or how the related goods and services supplied under the contract are to be valued, the Adjudicator must have regard to:

Regarding defective work, the Queensland Supreme Court has found that an adjudicator failed to perform the statutory duty under section 72(1)(b)(iv) of the BIF Act. This failure occurred because the contract did not specify how the work was to be valued, and although the adjudicator acknowledged the existence of some defects, they did not estimate the cost of rectifying those defects or consider this when determining the value of the construction work.

The NSW Supreme Court has also considered this in relation to the identical section under the NSW version of the BIF Act. Specifically, it was held, an “adjudicator would be required to set off, from the claimed amount, whatever amount he reached as the estimated cost of rectifying those of the defects…that he might find were proved to his satisfaction.”

A common argument between parties relates to whether the contract actually does provide for how the construction work is to be valued in the first instance. If it does, the adjudicator simply needs to value the work or related goods and services in accordance with the contract rather than the matters set out in sections 72(1)(b) and (2)(b).

The function demanded of an adjudicator under sections 88(1) and (2) of the BIF Act is to decide the adjudicated amount to be paid by the respondent to the claimant and the date on which the amount becomes payable together with any interest payable.

Previously, case law suggested that an adjudicator is not discharged from considering the merits of the claim, simply because no payment schedule has been provided. Although, the New South Wales Court of Appeal altered this position in 2023 in Ceerose Pty Ltd v A-Civil Aus Pty Ltd [2023] NSWCA 215 (Ceerose).

The position in New South Wales based on Ceerose is as follows:

... Certainly, it is not a jurisdictional error for an adjudicator, having decided all the reasons advanced by the respondent were invalid, to then and without more, determine the amount of the progress payment in favour of the claimant based on the payment claim.

More recently in 2025, the New South Wales Court of Appeal determined in Builtcom Constructions Pty Ltd v VSD Investments Pty Ltd as trustee for The VSD Investments Trust (No 2) [2025] NSWCA 134 that there is no rule prohibiting an adjudicator from considering material not supplied with a payment claim merely because the material would have affected the payment schedule, but that this is an error of law rather than a jurisdictional error that would result in invalidity of the adjudication decision or part thereof.

The decision of Ceerose has been considered in Queensland courts. Importantly, the result of Ceerose does not mean that the adjudicator is obliged to award the amount claimed without any consideration of the contract and merits. This was recognised by the Supreme Court of Queensland in Paladin Projects Pty Ltd v Visie Three Pty Ltd & Ors [2024] QSC 230, where the court stated at [112]: ...the decision [in Ceerose] does not in effect mean that the adjudicator must “rubber stamp” the claim if reasons in the payment schedule fall away.

In Taringa Property Group Pty Ltd v Kenik Pty Ltd [2024] QSC 298, the court noted that the adjudicator’s decision is often made up of multiple decisions regarding the individual issues and submissions made by each party in respect of the claims, observing: ...the scope of the duty to consider materials is determined by reference to the mandatory considerations of s 88(2) of the BIF Act; namely the relevant provisions of the BIF Act, the relevant construction contract, the payment claim, the payment schedule and each party’s properly made submissions.

Thus, while there may be few cases in which the breach of the duty to consider required matters is made out, that is not to say that there may not be circumstances in which the inference of omission to consider is demonstrated. Failure to refer to a submission on a centrally important matter, clearly articulated and based on uncontested facts, may demonstrate a failure to consider at all.

However, to successfully overturn an adjudicator’s decision, the New South Wales Court of Appeal emphasised in Martinus Rail Pty Ltd v Qube RE Services (No.2) Pty Ltd [2025] NSWCA 49 that both jurisdictional error and material injustice are required as the rough and ready nature of Security of Payment claims (which have tight deadlines) grants adjudicators leniency with respect to the legal reasonableness of their determinations.

The obligation of an adjudicator to decide an adjudication application in good faith was elaborated on in the NSW Court of Appeal. The court set out various bases for when an adjudication decision can be set aside, which included where the adjudication decision does not amount to an attempt in good faith to exercise their powers having regard to the subject matter of the legislation.

It is necessary for an adjudicator to consider the matters set out in section 88(2) if they are to fulfill their obligation of deciding an adjudication application in good faith. Examples of where an adjudicator was found not to have fulfilled this obligation are as follows:

In one case the issue concerned the adjudicator not acting in good faith, because:

In another case, it was apparent in the adjudication decision that the adjudicator had not considered one party’s submissions on a particular issue, with the court finding that had they done so, they could not reasonably have arrived at the result they did.

Aside from the issue of good faith, this also goes to the validity of the decision. This principle was considered by the Queensland Supreme Court when considering an adjudication decision, in which the adjudicator had allowed parts of the claims although the reasons provided no explanation, other than stating that the decision was made "after carefully considering the material and concerns”. The adjudication decision was ultimately set aside because the reasons did not demonstrate any analysis and were affected by jurisdictional error.

Inadequate reasons given in an adjudication decision may result in the decision being overturned in part or in full by the court. However, what is adequate will depend on the circumstances of the case.

Pursuant to section 95 of the BIF Act, an adjudicator is entitled to be paid an amount agreed between the adjudicator and the parties or an amount for fees and expenses that is reasonable having regard to the work done and the expenses incurred.

There is a maximum amount that can be charged by an adjudicator when the progress claim is for an amount that is not more than $25,000. There are various amounts set under the Regulation for claims up to that amount ranging from fees in the sum of $620 when the claim is for no more than $5,000 to $2,070 when the claim is more than $20,000 but not less than $25,000. Otherwise, there is no prescribed limit, however, the fees must still be reasonable. These amounts are subject to variation under the Regulation.

The usual process regarding fees is:

Even if the decision ends up being held to be invalid by a court, the adjudicator is still entitled to payment of their fees, but only if they acted in good faith when adjudicating the application.

Based on section 95(6) of the BIF Act, the courts in Queensland have determined that the preservation of the adjudicator’s right to retain their fees if the adjudication decision is declared void does not apply if the decision was not made in time.

Pursuant to section 90(2) of the BIF Act, if the adjudicator has determined that the respondent is to pay any amount to the claimant, the respondent is required to pay that amount to the claimant within five business days after the day in which the adjudicator gives a copy of their decision to the respondent, or any later date determined by the adjudicator.

The respondent also must notify the Adjudication Registrar of having made that payment and evidence of payment. If the respondent fails to pay, the claimant can:

Claimants generally only have one opportunity at adjudication in relation to any particular claim, provided that claim was valued by an adjudicator.

Under section 87 of the BIF Act, once particular work or related goods and services has been valued by an adjudicator under a construction contract, a later adjudicator must give those claims the same value as previously decided, unless the claimant or respondent can satisfy the adjudicator that the value of the work or goods and services has changed since the previous decision.

For this to impact a later adjudicator, there first needs to have been a valuation of the particular claim in an earlier adjudication. This position was confirmed by the NSW Supreme Court where the court said of the equivalent New South Wales provision that, it won’t be in all cases that there will have been a prior valuation. Here, despite the court finding that the adjudicator had not complied with the

NSW equivalent of section 87 of the BIF Act, the court did not consider that the adjudication decision was invalid as a result for jurisdictional error, as it was not considered an essential precondition to jurisdiction.

In Queensland, by operation of section 87 of the BIF Act and the principle of issue estoppel, an adjudicator in a subsequent adjudication will be bound to follow previous adjudicators valuations and findings of fact which were essential to the determination of the earlier decision.

That is, unless a claim (for an amount or item) is a different claim and progressed on the basis of additional material and submissions, an Adjudicator will be bound (by issue estoppel) insofar as a subsequent adjudication seeks to re-agitate issues which were essential to those prior determinations.

The doctrine was first recognised in the context of the security of payment legislation in NSW. The NSW Court of Appeal held that, in addition to the express words of the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1999 (NSW), common law principles in the nature of ‘issue estoppel’ and ‘res judicata’ would also operate to place limitations on subsequent adjudicators.

More recently the Queensland Supreme Court considered this issue in Karam Group Pty Ltd ATF The Karam (No. 1) Family Trust v HCA Queensland & Ors [2023] QSC 245. The court noted that, albeit the inconsistent position taken by interstate courts, there is agreement that a party may be prevented from arguing for a particular conclusion on an issue where that issue has been raised and decided in an earlier decision.

The elements required to establish whether the doctrine applies, was endorsed by the Queensland Supreme Court in 2010. Specifically, the party relying on the doctrine needs to prove:

In the above case, the court gave the following examples of where issue estoppel does not apply:

The South Australian Court of Appeal delivered a 2025 decision examining whether the principle of Anshun estoppel applies to later payment claims and adjudication determinations under South Australia’s SOP legislation. In Goyder Wind Farm 1 Pty Ltd v GE Renewable Energy Australia Pty Ltd & Ors [2025] SASCA 39, the Court held that neither common law issue estoppel nor the extended Anshun estoppel doctrine applies to subsequent claims or determinations made under the Act. As a result, in South Australia, claimants may pursue costs arising from the same delay event in later payment claims or adjudications, provided the costs sought do not overlap.

Pursuant to section 89 of the BIF Act, the adjudicator may, on their own initiative or if requested by one of the parties or the Adjudication Registrar, correct in their decision a clerical mistake, an error arising from an accidental slip or omission, or a material miscalculation of figures or a material mistake in the description of a person, thing or matter mentioned in the decision, or a defect of form (often referred to as the ‘slip rule’).

In Queensland, it has been held that the slip rule is available where the adjudicator makes an accidental or erroneous omission to consider a particular submission or to deal with part of a claim.

Unless it is an error of jurisdiction or arises out of a breach of natural judice or procedural fairness, the decision will remain effective and cannot be declared void by the court.

The position of the courts was summarised in a 2020 New South Wales Supreme Court case. That case reiterated the following which is applicable to the BIF Act:

Further, the New South Wales Court of Appeal decision in Martinus Rail Pty Ltd v Qube RE Services (No.2) Pty Ltd [2025] NSWCA 49 emphasised that to overturn an adjudicator’s decision, both jurisdictional error and material injustice are required.

On occasion, after the adjudication application is lodged and served, the parties settle their dispute.

In that situation, there is a mechanism under section 97 of the BIF Act for the claimant to withdraw their adjudication application by a written notice of discontinuance to both the adjudicator and the respondent.

There is a mechanism under section 94 of the BIF Act for the claimant to remake their application in very limited circumstances. This applies if the appointed adjudicator doesn’t decide the application within the required time. The claimant can either simply ask the Adjudication Registrar to refer their original application to a new adjudicator, or they can make a whole new application.

The Queensland Court of Appeal considered the above provision where it was noted that the entitlement of the claimant to either make a new application or have the original one referred to a new adjudicator, only applies if the adjudicator does not decide the application within the time required by section 85.58

However, this must be understood as including any extended period under section 86.

Further, the court observed that in circumstances where the adjudicator has not decided the adjudication application within the required time (including any extended time), the claimant need not withdraw their original application before either requesting the adjudicator to refer their application to a new adjudicator or making a new application.

However, there is a time limit of five business days for the claimant to take one of those steps, which runs from the date the adjudication decision was due.

One thing which is often overlooked, is who pays for the adjudicator’s fees up to the point of the withdrawal of the application. This question should be addressed and resolved by the parties in any settlement agreement, prior to the adjudication application being withdrawn.