24 February 2023

7 min read

On 10 November 2022, APRA released its discussion paper ‘Superannuation transfer planning: Proposed enhancements’ (Discussion Paper), proposing several changes to trustee obligations for successor fund transfers (SFTs). APRA is seeking comments by 10 March 2023.

There is a lot to absorb in the Discussion Paper. However, we thought it was a timely reminder that, back in 2012/2013, when trustees were preparing their MySuper authorisations (which was no small feat), trustees were required, under SIS section 29SAB, to give effect to what may be a transfer of MySuper members within a 90-day period, if their MySuper authorisations are cancelled.

This requirement is somewhat unclear because section 29SAB is ambiguous by virtue of only its heading, stating a MySuper transfer requirement, whilst the section’s law refers to a different requirement – being the requirement for trustees, who have their MySuper authorisation cancelled, to take action “required by the prudential standards” within 90 days. There are no prudential standards in respect of this requirement.

Problematic, also is that SIS section 55B states that governing rules preventing a trustee from giving effect to “an election made in accordance with section 29SAB (election to transfer assets attributed to a MySuper product if authorisation cancelled)” would be void. It is questionable whether section 55B is merely cross-referencing a heading or stating a requirement – some textbooks suggest it is a requirement.

The Discussion Paper certainly makes it clear that APRA will take steps to rectify this ambiguity or oversight, by formalising a 90-day MySuper transfer requirement.

A MySuper transfer gives rise to a SFT, even if the only transfer is the MySuper members and assets, and the choice products remain with the transferor fund. We have completed a number of SFTs, but not to a 90-day timeframe.

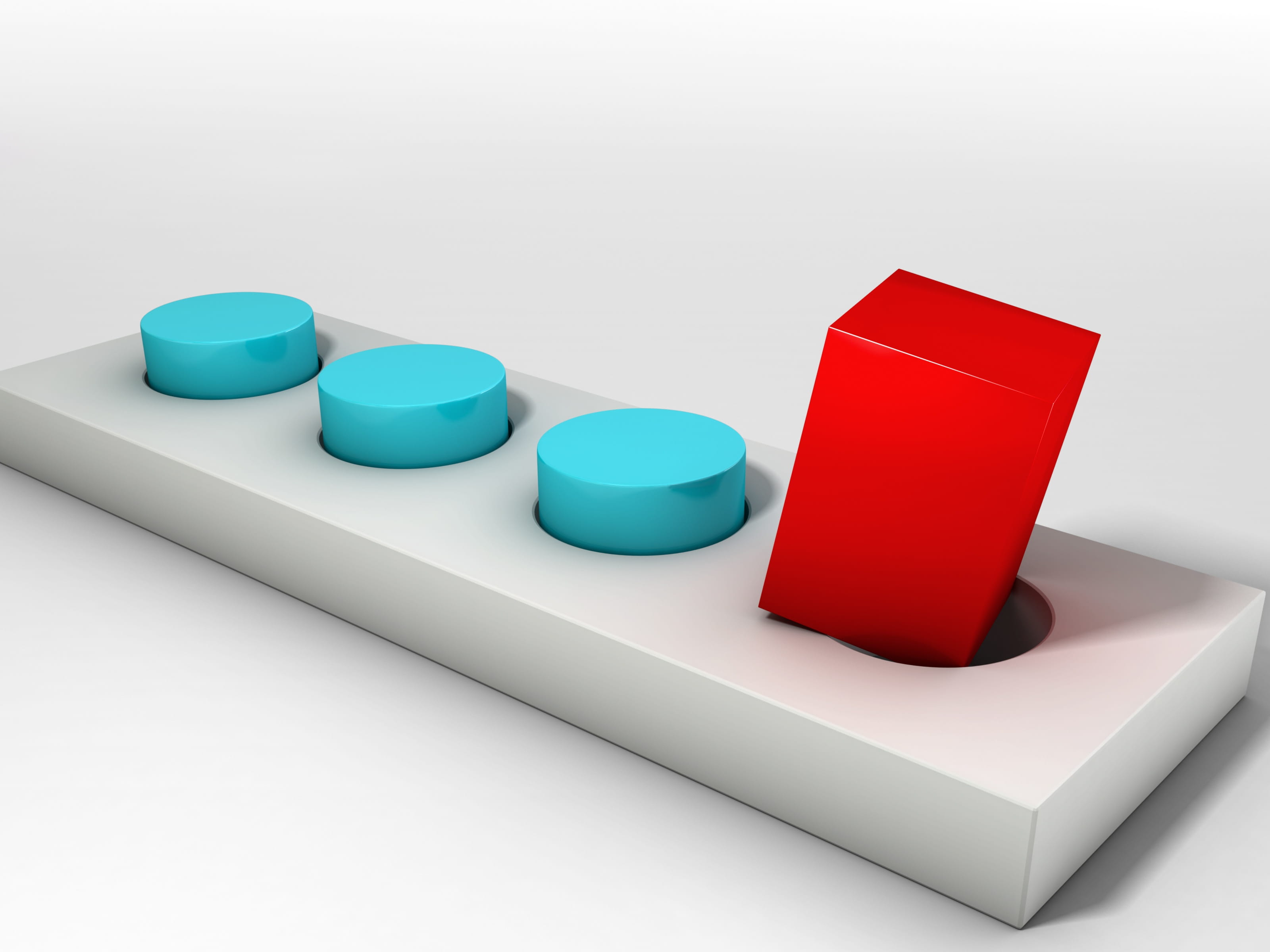

Whilst we agree with the tenor of APRA’s views on MySuper equivalency in its current Prudential Practice Guide SPG 227 – Successor Fund Transfers and Wind-ups, 90 days still appears quite ambitious (and this partly goes to why APRA is proposing that trustees pre-plan for such events). A MySuper transfer should, theoretically, give rise to a “round peg in a round hole” scenario, meaning that it may be possible to:

We refer to the “round peg in a round hole” scenario because MySuper is a standard accumulation product, referable to one investment option and relatively standard group insurance terms, meaning transferability across funds should be comparatively straight-forward, where those funds have relatively straight-forward structures (for example, there is no need to transfer MySuper members from various sub-plans or large employer MySuper products, for example). In such a case:

However, when considering the due diligence requirements (including investment due diligence and transfer of assets), the 90-day requirement would require both trustees to ensure their houses are in complete order to efficiently share their due diligence document suites, which includes subsequent requests for information, often from multiple sources within a fund. We question whether either party could scale back due diligence, which may depend on both parties’ risk tolerances, noting future liabilities are likely to impact some cohort of members.

Again, as the concept of a MySuper transfer seems like placing a round peg in a round hole, the SFT Deed would likely address the transfer of MySuper members and assets, the transfer of liabilities and indemnities relating to that transfer and nothing else – no product mapping, branding, staffing, group insurance issues and so on. This may reduce some burdens, but not all.

We think it unlikely that a transferor could only transfer its fund’s MySuper component, whilst retaining what probably would be a minority member-held choice product portfolio. This is where we question the 90-day requirement. In our view, a transfer of MySuper members and assets would most likely need to go hand-in-hand with the transfer of the choice members and assets. You cannot have one without the other (though there are situations in which this has occurred).

It would not be sustainable for a trustee to retain choice members without the cash flows and returns arising from the majority-held MySuper product. In other words, we could not imagine a case where a trustee, who has lost its MySuper authorisation, would seek to transfer the majority of its members and either retain the minority members and assets or seek to subsequently (and inevitably) transfer the minority members at a later stage. Here are some reasons why:

In other words, retaining or subsequently transferring these minority members, at a later stage, would likely expose trustees (transferors and potentially, transferees) to breaches of a number of SIS covenants whilst also acting against ordinary commercial sensibility.

Added to that problem is that, as soon as choice products enter the SFT equation, trustees invariably find themselves seeking to fit square pegs into round holes – it would be very ambitious to seek a 90-day SFT of both MySuper and the accompanying choice products when the pieces do not fit neatly.

On that basis, the 90-day MySuper transfer requirement may not work in practice whilst seeking to achieve the best financial interests of members of either the transferor fund or transferee fund, for the simple reason that a MySuper transfer would morph from a theoretical round peg in a round hole scenario to a far more complex situation.

To address this, could the transferor and transferee, as part of an overall SFT package, seek the 90-day transfer of MySuper members and then the subsequent transfer of the minority choice product members six to nine months later (assuming a 12-month SFT timeframe)? Theoretically, the answer could be “yes” (and we might see this happening), but we would assume that a prudent transferee would only agree to such terms if they were heavily conditioned in the transferee’s favour. Failure to provide an out clause on the residual choice component would likely expose the transferee to claims that it is in breach of the SIS covenant not to enter into any arrangement that would hinder it from properly performing its duties (and others in the SIS covenant suite).

Despite the 90 day rule, we welcome the certainty that APRA’s proposals provide. We assume that APRA will seek the 90-day MySuper transfer period, unless counter-arguments are brought to the table. If the 90-day MySuper timeframe becomes standardised, we assume that many trustees would need to discuss this with APRA and seek extensions, in good faith, if their MySuper authorisations were ever cancelled.

If you have any questions about this article, please get in touch with our team using the contact details below.

Disclaimer

The information in this article is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, we do not guarantee that the information in this article is accurate at the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future.