19 May 2021

8 min read

#Corporate Restructuring and Insolvency

Published by:

The recovery of preference payments is a key weapon in a liquidator’s arsenal and, since the introduction of safe harbour reforms in 2017 and the COVID-related suspension of insolvent trading liability (which narrow the scope for recovery from directors), are an increasingly important and prominent part of recovery work undertaken by liquidators.

In Badenoch Integrated Logging Pty Ltd v Bryant, in the matter of Gunns Ltd (in liq, recs and mgrs apptd) [2021] FCAFC 64 (10 May 2021) (Badenoch v Bryant) the Full Federal Court has made substantial changes to the landscape for preference claims. In Badenoch v Bryant, their Honours unanimously confirmed that:

These changes are a win for creditors as they create additional challenges for liquidators seeking to recover preference payments from creditors.

Badenoch v Bryant – the case

Gunns Ltd and its wholly-owned subsidiary Auspine Ltd (together, Gunns) went into liquidation in September 2012.

Since approximately 2003, Badenoch Integrated Logging Pty Ltd (Badenoch) was engaged by Gunns to provide timber harvesting and haulage services. Once Gunns went into liquidation, the liquidators sought to recover certain amounts paid to Badenoch using the preference payment provisions in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act).

Relevantly, during the six months before the date of appointment (relation-back period), Gunns made 11 payments to Badenoch. Among other things, Davies J at first instance was asked to consider:

During the course of the commercial relationship between the parties, Badenoch would provide services to Gunns and render monthly invoices for those services. Gunns’ level of indebtedness to Badenoch fluctuated from time to time as invoices were rendered and paid. In other words, there was a running account (in accordance with section 588F(3) of the Corporations Act) between the two parties. There was a dispute as to which of the 11 payments formed a part of this running account.

The liquidators of Gunns sought to maximise their recovery of preference claims from Badenoch in two ways:

Continuing business relationship

The running account treats all the transactions forming part of a CBR as a single transaction to determine whether there has been an unfair preference to a creditor. The preference claim available to the liquidator is the net difference between the transactions contained in the running account as a whole. Practically, this often has the effect of reducing the overall amount recoverable by liquidators in contrast to seeking to recover individual payments.

Whether a CBR exists in any given set of circumstances is a matter of fact. Where the circumstances of a particular payment show that it was made not as an integral part of a continuing supply of services but was made for the primary purpose of payment or partial repayment of a past debt, that is an indication that the CBR has come to an end and that payment will not form part of the running account.

Courts have long recognised that payments made by a company can serve the dual purposes of reducing indebtedness and securing future supply.[1] The test is whether the ‘ultimate effect’ of the transactions was ‘forward-looking’, to secure provision of continuing services or supply of goods, or ‘backward-looking’, to discharge existing indebtedness.[2]

At first instance, Davies J held that Badenoch's conduct in relation to the first two payments, which included a letter of demand, threats of legal action, and a ‘stop credit’, or ‘hold’ on further supply, broke the CBR. As a matter of fact, her Honour found that the CBR was revived for later payments.

In Badenoch v Bryant, the Full Federal Court recognised that there will be times in business relationships where measures such as demands or supply halts may be taken, but that these actions may still be predicated on an intention and belief that the business relationship is and will be ongoing.

Peak indebtedness

Section 588FA(3) of the Corporations Act codifies the historical common law doctrine of the running account. The common law included what has come to be known as the ‘peak indebtedness’ rule. This rule allowed liquidators to elect the date in the relation-back period, invariably the date that the debt was at its highest, in calculating the value of a preference claim in a running account, thereby maximising the recoverable amount.

Until Badenoch v Bryant, courts had acted on the basis that the codification did not change the law of running account and the peak indebtedness rule still applies.[3]

However, in Badenoch v Bryant, the Court rejected the ‘peak indebtedness’ rule as a matter of construction on the basis that:

Thus the Full Federal Court explicitly overruled the decisions that followed the enactment of section 588FA(3) in 1989 insofar as they applied the peak indebtedness rule to section 588FA(3).

The effect of this clarification is as follows:

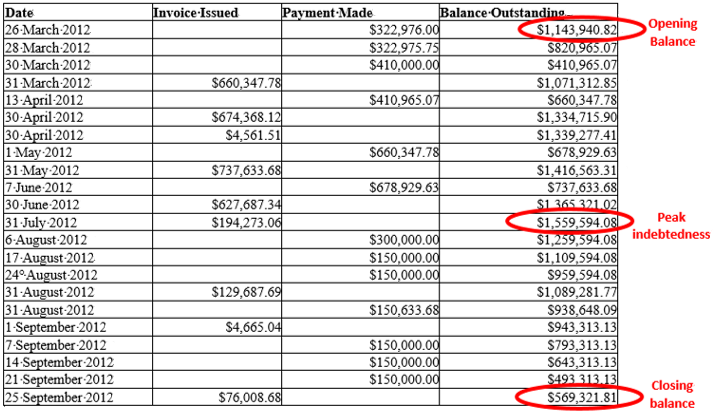

Under the old peak indebtedness test, the liquidators could select any date within the relation-back period and take the difference between that peak indebtedness and the balance of the account on the appointment date. In this case, the difference was $990,272.27.

Under the Full Court’s methodology, the balance on the appointment date is deducted from the balance at the start of the relation-back period (six months before). In the above scenario, this equates to $574,691.01.

The clarification of the running account rule, therefore, reduces the liquidators’ preference claim by $415,653.26.

What does the decision mean?

The decision in Badenoch v Bryant has substantially changed the landscape of preference claims in favour of creditors.

The Full Federal Court affirmed that the core enquiry is whether payments during the relation-back period contemplate, and are in expectation of, a CBR, or whether their “real purpose is recovery of past indebtedness”.

But their Honours also warned that courts should not “take an unduly restrictive approach” to identifying a CBR. Following Badenoch v Bryant, we anticipate courts will be likely to take a more practical, commercial view of the running account concept on the bases that:

The better view is that a court will look to the payments and surrounding circumstances as a whole to determine whether a CBR existed rather than viewing particular transactions more narrowly.[4]

And, once a running account is established, liquidators can no longer nominate a date within the relevant period that maximises their preference claim. The entire transaction during the relation-back period must be considered and liquidators can no longer elect to include certain payments and to reject others.

If you would like to discuss how these changes may affect your specific circumstances, we invite you to contact a member of our team.

[1] See, eg, Sands & McDougall Wholesale Pty Ltd (in liq) v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) [1999] 1 VR 489, [43]

[2] See, eg, Airservices Australia v Ferrier (1996) 185 CLR 483; VR Dye & Co v Peninsula Hotels Pty Ltd (in liq) [1999] 3 VR 201.

[3] Cashflow Finance Pty Ltd v Westpac Banking Corporation [1999] NSWSC 671, [507] (Einstein J); Re Employ (No 96) Pty Ltd [2013] NSWSC 61; (2013) 93 ACSR 48; Olifent v Australian Wine Industries Pty Ltd (1996) 130 FLR 195; 19 ACSR 285 (SASC); Sands & McDougall Wholesale Pty Ltd (in liq) v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) [1999] 1 VR 489, [40].

[4] Sutherland v Lofthouse (2007) 64 ACSR 655, [46]. See also Richardson v The Commercial Banking Company of Sydney Ltd (1952) 85 CLR 110, 133.

Disclaimer

The information in this publication is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, we do not guarantee that the information in this article is accurate at the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future.

Published by: