31 August 2022

6 min read

Published by:

The Fair Work Commission (FWC) has ruled that a Deliveroo delivery driver did not classify as an employee in an unfair dismissal claim that was subsequently overturned. The decision will undoubtedly be a reference point for the current discussions between industry groups regarding the Federal Government’s proposal to vest the FWC with powers to create safety net wages and conditions for workers in the gig economy who are not recognised as employees.

Earlier this year, the High Court handed down two landmark decisions, clarifying the distinction between employees and independent contractors (see related article). In the decision of Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union & Anor v. Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 1 (Personnel Contracting) and ZG Operations Australia Pty Ltd & Anor v. Jamsek & Ors (Jamsek), the High Court ruled that where parties have entered into written agreement in which the rights and obligations of the parties are comprehensively established, the characterisation of the relationship is determined solely by reference to those rights and obligations under that agreement, and not through an assessment of how the relationship operates in practice.

In Diego v Deliveroo Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FWCFB 156 (Deliveroo’s case), the worker’s engagement was regulated by a written agreement that comprehensively set out the contractual rights and obligations of the parties. Applying the High Court decision in Personnel Contracting and Jamsek, the Full Bench determined the question of whether the worker was an employee of Deliveroo at the time of his termination by reference to the terms of the written agreement. This resulted in a finding that the delivery rider was an independent contractor rather than an employee and was not afforded protection from unfair dismissal under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act).

A delivery rider commenced working for Deliveroo pursuant to a ‘supplier agreement’ in 2017. In April 2020, the worker’s agreement with Deliveroo was terminated on the grounds that the worker failed to deliver orders in a reasonable time. The worker lodged an unfair dismissal application under section 394 of the FW Act.

The two main issues in this case were:

Deliveroo rejected the worker’s claim on the basis that the worker was an independent contractor, not an employee. Therefore, he could not be protected by the unfair dismissal provisions under the FW Act.

At first instance, Commissioner Cambridge of the FWC ruled in favour of the worker, finding that he was an employee and as such, was a person who was ‘protected from unfair dismissal’ within the meaning of section 382 of the FW Act. Further to this, Commissioner Cambridge found that the dismissal was harsh, unjust and unreasonable.

In determining his status as an employee, Commissioner Cambridge applied the multifactorial test set out in Hollis v Vabu Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 44, and placed emphasis on the level of control exercised by Deliveroo over the rider. Other factors pointing to an employment relationship were the use of branded clothing and that the work performed was low skilled.

An order was made for reinstatement, continuity of service and restoration of his lost pay.

In June 2021, Deliveroo lodged an appeal against the decision of Commissioner Cambridge on the basis that the Commissioner erred in finding that the delivery rider was an employee. However, the determination of the appeal was deferred until the High Court decisions in Personnel Contracting and Jamsek were handed down.

On appeal, the Full Bench found that Commissioner Cambridge’s decision no longer reflected the current state of the law, and applied the principles set out in Personnel Contracting and Jamsek as follows:

However, the FWC in Deliveroo added to this a further proposition, namely, that a contractual freedom on the part of the party performing the relevant work to accept or reject any offer of work and to work for others is not necessarily a contraindication of employment and may rather be consistent with casual employment.

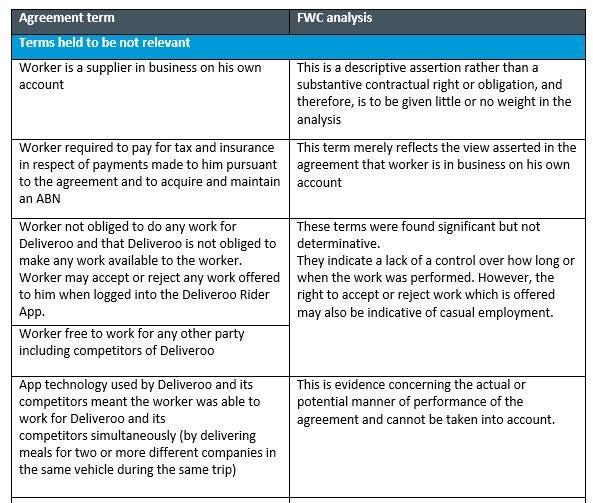

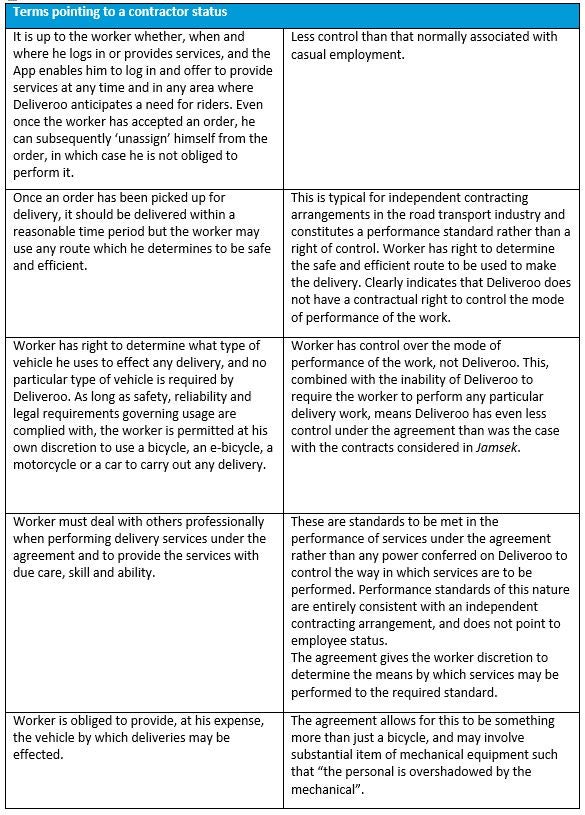

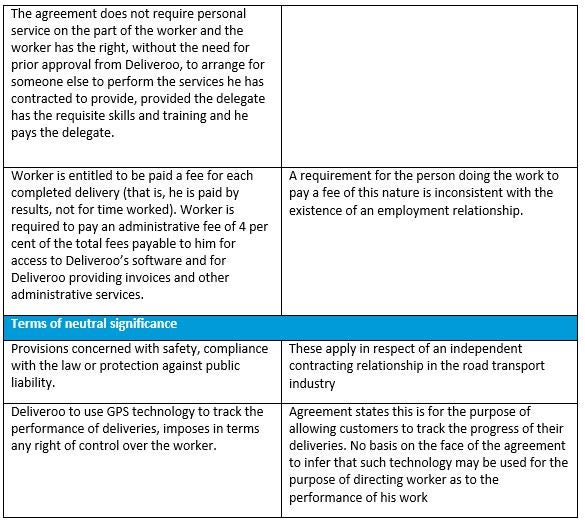

The approach taken to each term is examined in the table below:

Applying the ‘contract primacy’ principle in Personnel Contracting and Jamsek, the FWC held that the features of the agreement weighed in favour of a characterisation the worker was an independent contractor.

The FWC observed the Personnel Contracting decision obliged the FWC to ignore certain realities concerning way in which the working relationship between the worker and Deliveroo operated in practice (i.e. the significant degree of operational control over its delivery workers). These matters, taken together, would tip the balance in favour of a conclusion the worker was an employee of Deliveroo. However, as a result of Personnel Contracting, the FWC “must close [its] eyes to these matters.”

The FWC also observed this left the worker with no remedy he can obtain from the FWC for what was, plainly in its view, unfair treatment on the part of Deliveroo.

This FWC decision provides clarity to the characterisation of a gig worker status in light of the principles set out by the High Court in Personnel Contracting and Jamsek. Undoubtedly, this case will have important ramifications for work arrangements in the gig economy.

This case is a reminder of the complexities faced by those engaging independent contractors and sends a strong message for employers to:

If you have any questions about the decision or require any assistance, please get in touch with us below or contact our team here.

Authors: Charles Power & Fiorella Chiavetta

Disclaimer

The information in this article is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, we do not guarantee that the information in this article is accurate at the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future.

Published by: