24 June 2019

8 min read

The landmark Shergold Weir Report 'Building Confidence', which was made public by the Building Minister’s Forum (BMF) in April 2018, recommended several important changes to the construction industry, some of which might have implications for certifiers generally. Registered Professional Engineers of Queensland (RPEQs) should take note, as this might be a sign of things to come.

Background

In mid-2017, the BMF (which oversees policy and regulatory issues affecting Australia’s building and construction industries) requested an assessment of the effectiveness of compliance and enforcement systems for the building and construction industry across Australia. This seems partly to have been commissioned as a reaction to incidents like the Melbourne Lacrosse Tower Fire in 2014. The result was the Shergold Weir Report 'Building Confidence'.

Melbourne Lacrosse Tower Fire in 2014

Facts

The case involved the spread of fire up the external wall cladding to the roof of the tower from an apartment whose resident had left a cigarette butt in a plastic food container sitting on a timber surfaced balcony table. Investigations showed that a contributing cause to the rapid vertical spread of fire was the combustible external aluminium wall cladding on the side of the building.

Decision

In the first test case regarding liability for the installation of combustible cladding, the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (tribunal) determined that the use of aluminium composite panels (ACPs) with a highly combustible 100 per cent polyethylene (PE) core to clad the façade of the Lacrosse Building did not comply with the Building Code of Australia (BCA).

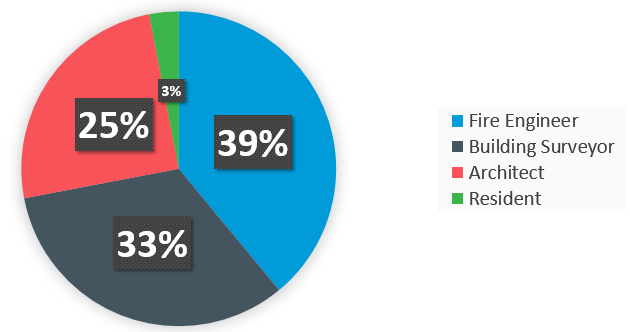

Over a 227 page judgement, the tribunal examined the roles, responsibilities and percentage culpability of a number of relevant parties including the Architect, the Building Surveyor, the Fire Engineer, the Builder, the Superintendent, the Resident of the Apartment and the Resident’s Flatmate.

The primary liability to pay damages fell on the Builder who had proposed the use of the ACP Alucobest in response to the Architect’s specification and had sourced and installed it, although it was able to recover from a number of parties:

Reasoning for decision

The Fire Engineer was the primary consultant responsible for fire safety compliance and had provided the fire engineering services and, in particular, had provided fire engineering reports to the Surveyor prior to the Surveyor issuing the permit to build.

The Building Surveyor had issued the building permit to construct the building.

The Architect had originally specified ACPs as a compensate panel indicative to Alucobond but approved the sample of the Alucobest cladding material eventually used.

Ultimately the tribunal found that the Builder, the Architect and the Surveyor each had sufficient information about the potential combustibility of ACPs “but, for a variety of reasons, they each failed to identify or conclude the ACPs were non-compliant”. The tribunal then drew a distinction with the Fire Engineer – who bore the lion’s share of liability – because it “failed to conduct the investigations and assessments necessary to confirm the relevant features of the ACPs proposed for use [but] had it done so, it would have come to a different conclusion about compliance to that reached by these other parties”.

In relation to the Fire Engineer, the Tribunal Member made the following quite pointed comments:

“It is worth observing that the reason for this apparent disconnect between Mr Nicolas’s evidence of what he understood his role to be, compared to the terms of the contract he signed, may have been hinted at by his reference to the use of templates. My impression generally of Thomas Nicolas’s approach to the FERs and other documents, was that there were a number of instances of the use of template or “boilerplate” language (as well as reference to out-of-date guidelines), without much attention being given to what the words actually meant or required. Thomas Nicolas is, of course, not alone in this. It is often the case that diligent and competent professionals blithely reuse standard documents that have served them well over the years, focusing only on those parts that need to be tailored to each job. It is only when something goes wrong and the lawyers become involved, that any real attention is given to how that boilerplate language informs potential liability.”

Recommendations

The Shergold Weir Report focuses on shortcomings in the implementation of the National Construction Code and addresses compliance and enforcement systems for building and construction standards.

It concluded that there are an increasing number of issues related to the construction industry that diminish public confidence that the building and construction industry can deliver compliant, safe buildings that will perform to the expected standards over the long term. It came up with 24 recommendations including the following key recommendations:

A year on from the Report, and the BMF has released its implementation plan. The plan outlines a road map for reform, including target time frames, but it recognises that all jurisdictions, whilst committed to making reforms, are not at the same stage. The timing of the reforms will need to be tailored to the different regulatory systems in the states and territories.

Queensland is well along its implementation path, and seems particularly focused on improving public confidence, but then it has previous experience, having already formulated the Professional Engineers Act 2002 (Qld).

There has also been general acceptance of the Report’s recommendations by the building and construction industry, including the recent legislative reform regarding non-conforming building products via the Queensland Building and Construction Commission Act 1991 (Qld) (QBCC Act). This places duties on the supply chain to ensure that building products used in Queensland are safe and fit for their intended purpose.

The QBCC Act seeks to ensure that non-conforming building products are not used by requesting that “required information’ regarding the building products installed is provided by the relevant “person in the chain of responsibility”. It also imposes a duty on any “person in the chain of responsibility” to notify the Commission if it becomes aware or suspects that a building product is non-conforming for an intended use.

Certifiers?

The BMF has now prioritised six recommendations that it believes would benefit from a consistent national approach. Each jurisdiction should:

This arguably looks a bit like a supercharged version of the requirements already imposed on RPEQs under the PE Act. The question then is, assuming the Queensland Government continues the implements process, will this involves two similar parallel regimes (one for RPEQs and one for building professionals), or is this an opportunity to improve both systems of regulation at the same time?

Conclusion

It is evident that there is an increasing focus on regulation, compliance and enforcement in the construction industry, especially for certifiers, which is attracting attention at all levels of government. While none of us set out to be test cases, the opportunity to learn that comes along with increased regulation (especially if national registration of certifiers is required) is to be welcomed. The industry as a whole, and certifiers in particular, need to be aware of their individual obligations as they evolve, or risk being exposed to increasing liability, insurance and perhaps even front page scrutiny.

Authors: Suzy Cairney & Megan Lewis

Contacts:

Brisbane

Suzy Cairney, Partner

T: +61 7 3135 0684

E: suzy.cairney@holdingredlich.com

Troy Lewis, Partner & National Head of Construction and Infrastructure

T: +61 7 3135 0614

E: troy.lewis@holdingredlich.com

Stephen Burton, Partner

T: +61 7 3135 0604

E: stephen.burton@holdingredlich.com

Melbourne

Stephen Natoli, Partner

T: +61 3 9321 9796

E: stephen.natoli@holdingredlich.com

Kyle Siebel, Partner

T: +61 3 9321 9877

E: kyle.siebel@holdingredlich.com

Sydney

Scott Alden, Partner

T: +61 2 8083 0419

E: scott.alden@holdingredlich.com

Christine Jones, Partner

T: +61 2 8083 0477

E: christine.jones@holdingredlich.com

Helena Golovanoff, Partner

T: +61 2 8083 0443

E: helena.golovanoff@holdingredlich.com

Disclaimer

The information in this publication is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, we do not guarantee that the information in this publication is accurate at the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future. We are not responsible for the information of any source to which a link is provided or reference is made and exclude all liability in connection with use of these sources.