22 March 2023

7 min read

Published by:

Last year, the High Court handed down two landmark decisions, Personnel Contracting1 and Jamsek2 (the High Court Decisions), clarifying the distinction between employees and independent contractors (see our previous article ‘Contractor vs employee: The new legal approach’).

The High Court departed from the longstanding traditional multi-factorial test used by the courts to determine whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor. The multi-factorial test focuses on the indicia of employment with reference to both the terms of the contract and how it was performed by the parties. The approach prescribed in the High Court Decisions focuses on the parties’ rights and duties under the contract as it was formed. The High Court held that if a comprehensive written contract is in place, the ultimate characterisation of the relationship will be focused on rights and duties established by the written contract rather than how the relationship operates in practice.

However, the High Court Decisions left undetermined the approach the courts should take in the absence of a written agreement.

The recent case of Muller concerned an unfair dismissal application in which the court had to consider the application of the multi-factorial test to determine whether a worker is an employee or independent contractor in the absence of a written agreement.

A photographer and a hardware store company (Timbecon) entered into an oral agreement for the creation of photographic and video content. Timbecon was initially recruiting for an employee, but during a negotiation meeting, the parties agreed, at the photographer’s request, that he would be engaged as a contractor so that he could continue providing photographic services to third parties.

The photographer commenced at Timbecon in November 2016, working three full days per week as per the original agreement. In January 2017, Timbecon asked the photographer to increase his hours to a full-time equivalent, and the photographer agreed. After the increase in his work hours, the photographer no longer worked for third parties, except for sporadic weekend work at weddings.

In February 2022, due to some performance concerns, Timbecon decided to terminate the photographer’s engagement, without giving him any notice. The photographer then brought an application alleging that he was unfairly dismissed.

The issue before the court was whether the photographer was entitled to protection from unfair dismissal under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). The court had to determine whether the photographer was an employee or a contractor to answer this question.

The Deputy President considered the applicable legal principles and recognised the relevance of the High Court Decisions in determining whether the photographer was an employee or an independent contractor. However, the Deputy President pointed out that the contract between the parties was wholly oral, which was a key point of distinction from High Court Decisions.

The main issues in this case were the following:

1. variation

The Deputy President found that the contract was initially formed in September 2016 and subsequently varied in January 2017, such that the photographer’s working days increased from three to five days per week. Notably, he did not consider that the contract had been varied to allow Timbecon to exercise a greater degree of control over the photographer or to diminish the photographer’s capacity to work in his own business.

2. traditional indicia

The Deputy President considered the characterisation of traditional indicia, including the existence of a right to control and the “own business/employer’s business” dichotomy. He noted that Personnel Contracting case confirmed that while these elements are significant matters, it remained appropriate to consider the “totality” of the relationship between the parties, albeit as framed by the rights and duties established by the parties’ contract.

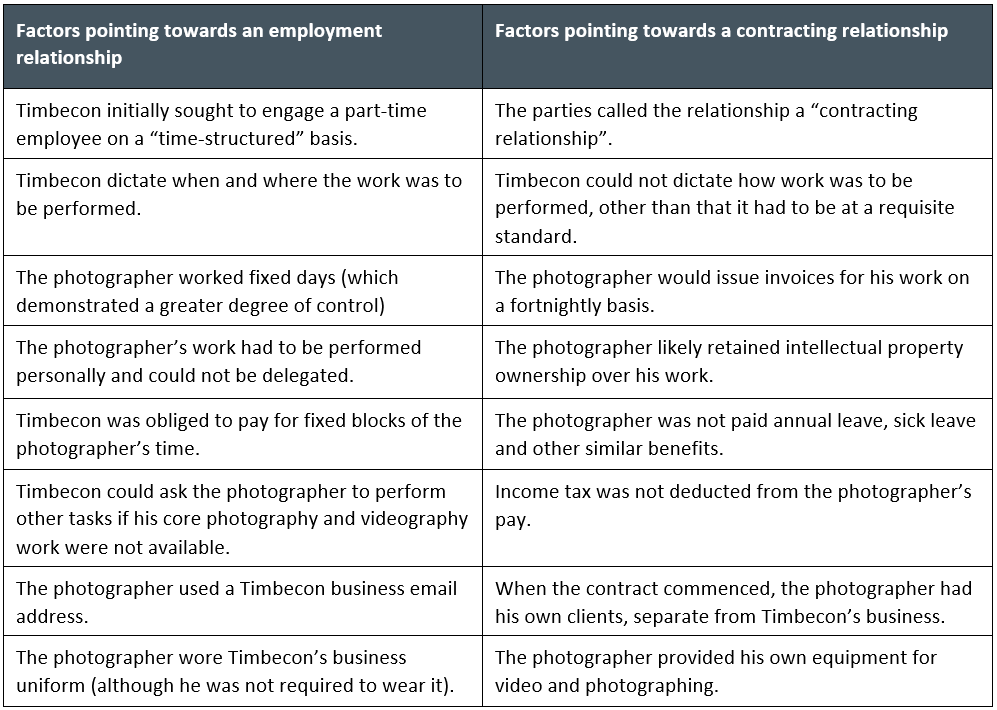

After asserting the express and implied terms of the agreement, the Deputy President proceeded to characterise the contract, identifying aspects pointing towards and against an employment relationship. We summarise key aspects in the table below.

The Deputy President found that although there were some work practices suggestive of an increased level of control, they did not rise to a level that manifested an assumption of a right of control over the photographer that was sufficiently different from the terms of the contract initially agreed.

Further, although the photographer was performing more work for Timbecon’s business than his own business following the variation, there was no term in the contract which required the photographer to work exclusively for Timbecon.

3. post-formation conduct

The Deputy President agreed with the High Court’s approach that post-formation conduct cannot, as a general rule, be admitted for the purpose of construing the contract, and that such conduct may only be relevant and available in limited exceptions (i.e. when there is doubt about contract formation, to ascertain the scope of the terms of an oral contract and to prove variation in the contract). However, the Deputy President held that the terms of the contract as varied in January 2017 (i.e. wearing uniform or attending work meetings) cannot be added to or subtracted from by reason of post-contractual conduct.

4. the use of ‘labels’

The Deputy President noted the High Court Decisions had confirmed that recourse to the parties’ description of the arrangement should be approached cautiously (and in many cases, not at all). However, in this case the Deputy President considered it was appropriate to have regard to the parties’ own characterisation of the contract as a factor relevant to the whole of the contract. The ‘label’ given to the relationship was not being treated as a “tie-breaker” or a determinative factor, but it could “shed light on the objective understanding of the operative provisions of their contract”. That objective was for the photographer to remain a contractor, while working on fixed days for Timbecon.

After considering the totality of the relationship between the parties, the Deputy President concluded the contract was initially formed as an independent contracting arrangement, and that the variation did not change the characterisation. The Deputy President dismissed the photographer’s unfair dismissal application.

On appeal, the Full Bench of the Fair Work Commission found that the Deputy President correctly applied the right legal principles in determining whether the photographer was an employee or independent contractor, as enunciated in the High Court Decisions. The Full Bench ruled the Deputy President was correct in emphasising the terms of the contract as originally agreed and not treating the post-contractual conduct as amending the character of the relationship despite varying the terms of the contract. This approach, according to the Full Bench, aligned with High Court precedent. To accept the appellant’s argument would be to restore the multi-factorial test, focusing improperly on the indicia of employment as opposed to the parties’ rights and duties under the contract as it was formed.

Therefore, the Bench confirmed the Deputy President’s conclusion that the photographer was not an employee and dismissed the appeal.

The recent decision of Muller confirms that courts will, as they are required to do, continue to apply the new common law approach of the High Court, even in the absence of a written contract.

This decision highlights that, although post-contractual conduct is capable of resolving a dispute concerning the existence of a particular term in an oral contract, it cannot be relied upon to establish the terms of that contract. Doing so would be, in effect, reverting back to the multi-factorial test, which focuses on the indicia of employment as opposed to the parties’ rights and duties under the contract as it was formed.

The decision also emphasises the need for parties to ensure that their agreements are in writing and comprehensively set out the intentions of the parties, as the focus will be placed on the rights and duties established by the contract rather than how the relationship operates in practice.

If you have any questions about an employment contract, please get in touch with our national Workplace Relations & Safety team below.

Disclaimer

The information in this article is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavour to provide accurate and timely information, we do not guarantee that the information in this article is accurate at the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future.

1 Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union & Anor v. Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 1

2 ZG Operations Australia Pty Ltd & Anor v. Jamsek & Ors [2022] HCA 2

Published by: